One of Windows kernel subsystem I recently dug into is the Configuration Manager (CM), mostly because I found very scarce public resources about it despite its criticality: this subsystem is responsible for managing the configuration of all Windows resources, and in user-land is exposed via a very familiar mechanism, the Windows Registry. It is a pretty well documented user-land mechanism, and so is its kernel driver API. My curiosity was around its inner working, and all the few (but brilliant) resources can be found in the link section below.

What I wondered was: How is the registry handled in the kernel by the CM? So in the same way that I explored other Windows subsystems, I tried to keep a practical approach, and the result was this WinDbg Js script, RegistryExplorer.js [1] that’ll be referring to throughout this post. This script allows to browse and query via LINQ the registry in a kernel debugging session.

This is a collection of notes, do not blindly trust, assume mistakes. Also, you’ll find the KD commands are given to reproduce easily, but your offset/index may vary. Last, everything was done/tested against Windows 10 x64 1909: I assume those findings to be applicable to other versions, but it may not be the case.

Overview

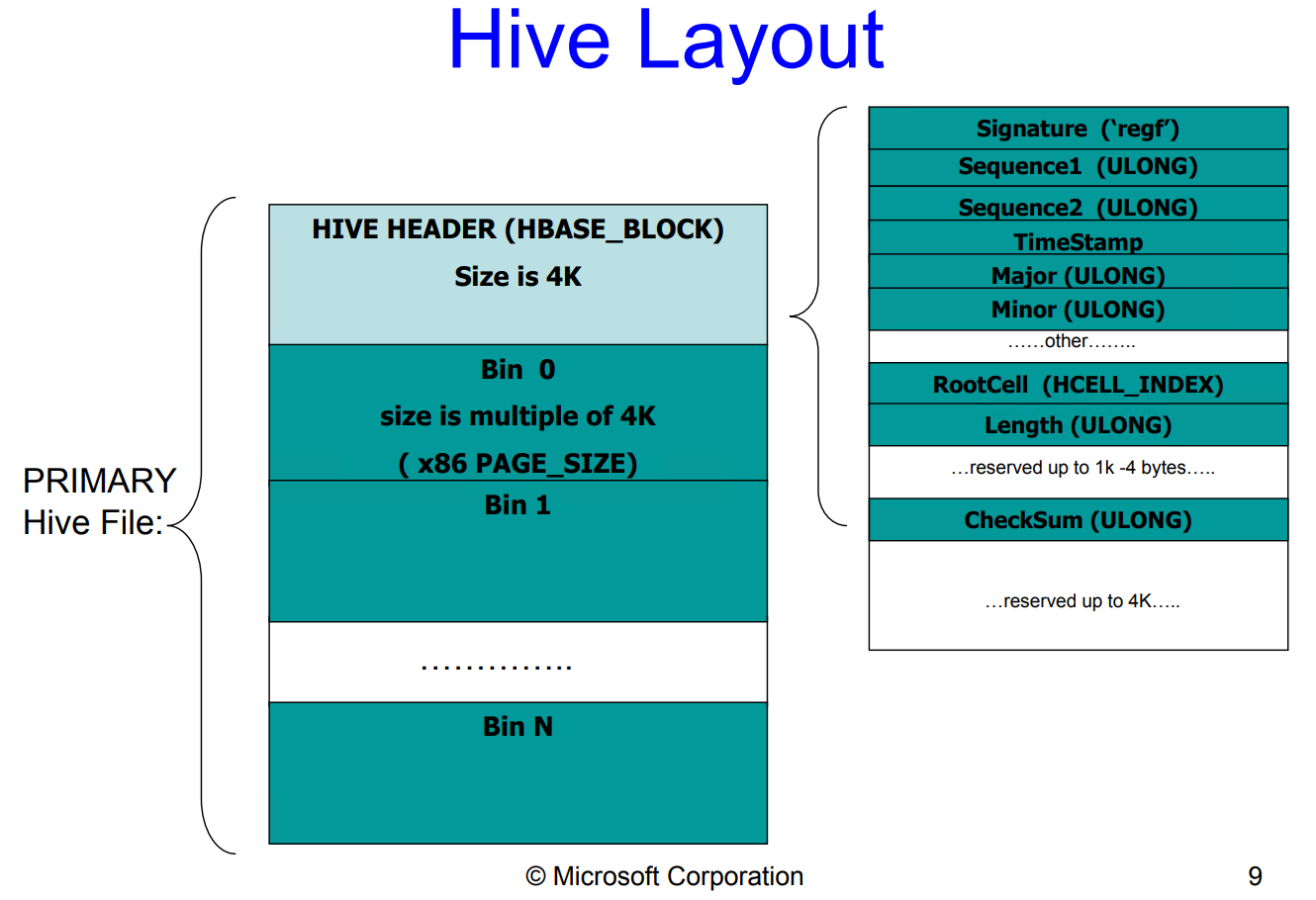

The Registry consists of a set of regular structures called “Hives”. Off-memory, they live in regular file (usually but not necessarily suffixed as .dat - ex: %USERPROFILE%\NTUSER.dat). Each .dat file operates as a small File System with its own hierarchy and nomenclature:

- Registry: Collection of (2) Hives (+ metadata) →

PRIMARY+.LOG - Hive: Collection of Bins (+ metadata), follows a tree structure

- Bin: Collection of Cells (+ metadata), bin size must be aligned to

PAGE_SIZE - Cell: Basic unit of allocation for the registry (contains raw data). The Cell size is declared as the 1st ULONG of the memory area. Those are critical, we’ll develop how below.

As a tree, a Hive can be browsed, exposing:

- Keys (or Key Nodes), comparable to Directories in the traditional FS world

- Values (comparable to Files), each of which can have one of 12 types:

REG_NONE,REG_SZ,REG_EXPAND_SZ,REG_BINARY,REG_DWORD_LITTLE_ENDIAN,REG_DWORD,REG_DWORD_BIG_ENDIAN,REG_LINK,REG_MULTI_SZ,REG_RESOURCE_LIST,REG_FULL_RESOURCE_DESCRIPTOR,REG_RESOURCE_REQUIREMENTS_LIST,REG_QWORD_LITTLE_ENDIAN,REG_QWORD

Therefore a Key can contain Sub-Keys but also Values, just like a folder can contain sub-folders and files. Later on, we’ll explain how to enumerate them, as we must go over some pre-requisites first. It could be noted that the analogy of a typical File System is true to the point where it is possible to abuse some situations via Symbolic Links (exploiting REG_LINK types) but we won’t be covering that today.

For convenience, the following equivalence will be used throughout this post:

- Top-Level Keys = Root Keys

- Sub Keys = Keys (as long as they aren’t Root Keys)

The best structure definition of a Hive I could find comes from “Windows Kernel Internals NT Registry Implementation”[2] (you’ll find many references to the PDF in this post).

Some hives are loaded very early in the boot process, as the BCD needs to retrieve its configuration settings from it in the CM hive; and also during kernel loading, hardware info are exposed from the HARDWARE hive. Once parsed and loaded from file to memory, all the system hives are linked via a LIST_ENTRY whose head is pointed by the exposed symbol nt!CmpHiveListHead, and can be iterated over as a list of nt!_CMHIVE object using the nt!_CMHIVE.HiveList field. Therefore a quick parsing can be done with our best friends WinDbg + DDM, which allows us to do some LINQ magic:

0: kd> dx -s @$hives = Debugger.Utility.Collections.FromListEntry(*(nt!_LIST_ENTRY*)&nt!CmpHiveListHead,"nt!_CMHIVE","HiveList")

0: kd> dx @$hives.Count()

@$hives.Count() : 0x1f

0: kd> dx -g @$hives.Select( x => new { CmHiveAddress= &x, HiveName=x.HiveRootPath} )

====================================================================================================

= = (+) CmHiveAddress = (+) HiveName =

====================================================================================================

= [0x0] - 0xffffa70284240000 - "" =

= [0x1] - 0xffffa702842d2000 - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SYSTEM" =

= [0x2] - 0xffffa70284340000 - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\HARDWARE" =

= [0x3] - 0xffffa70284d14000 - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\BCD00000000" =

= [0x4] - 0xffffa70284cec000 - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SOFTWARE" =

= [0x5] - 0xffffa702848e3000 - "\REGISTRY\USER\.DEFAULT" =

= [0x6] - 0xffffa70287c43000 - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SECURITY" =

= [0x7] - 0xffffa70287d46000 - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SAM" =

= [0x8] - 0xffffa7028806a000 - "\REGISTRY\USER\S-1-5-20" =

[...]

which looks familiar. This command exposes all the _CMHIVE objects loaded by the kernel, but hives themselves can be manipulated via their handle of type _HHIVE (accessible from nt!_CMHIVE.Hive) which allows, thanks to callback members (i.e. function pointers in the structure), to declare how to get access to data, allocate/free new nodes, etc.

Accessing the registry

An essential pre-requisite to understand how values are accessed in the kernel, is to understand 2 critical structures: Cells and Key Nodes (for now).

According to “Windows Kernel Internals NT Registry Implementation”[2], a Cell (p.12) is:

- The unit of storage allocation within the hive […]

- Used to store raw data, and build up logical data

- Keys, values, security descriptors, indexes etc all are made up of cells

- Fetching in a key, might involve several faults spread across the hive file

A Key Node (of internal type nt!_CM_KEY_NODE) is the structure inside the tree that will allow to access Cells (don’t worry Cells will be amply covered below - for now just think of it as the raw data). For a given key node, its Values (~files) are pointed by the field nt!_CM_KEY_NODE.ValueList, of type nt!_CHILD_LIST; and its subkeys (~sub-folders) via nt!_CM_KEY_NODE.SubkeyLists. This is always true, except for symbolic links (type = REG_LINK), which will dereference the node they point to via the field nt!_CM_KEY_NODE.ChildHiveReference.

So when by browsing a key node, what to pay attention to are:

- the SubKey list (i.e. ~subfolders)

0: kd> dt _CM_KEY_NODE

nt!_CM_KEY_NODE

[...]

+0x014 SubKeyCounts : [2] Uint4B

+0x01c SubKeyLists : [2] Uint4B

[...]

- the Value list (i.e. ~files)

0: kd> dt _CM_KEY_NODE

nt!_CM_KEY_NODE

[...]

+0x024 ValueList : _CHILD_LIST

[...]

0: kd> dt _CHILD_LIST

nt!_CHILD_LIST

+0x000 Count : Uint4B

+0x004 List : Uint4B

And looking up a specific Value can be summarized as such:

Source[2]

Source[2]

As we see from the symbols, Value and SubKey lists are not designated by direct pointers in memory, but instead by indexes. Those indexes point to Cells, which contains either the data itself or the next key node to parse to reach the data. We’ve kept mentioning Cells without covering it, it now becomes important to do so, know how Cells are, how they work and how they can be accessed.

Cells

The Cell is the basic storage unit for a Hive: what this means is that all data of the hive can be found by knowing 2 pieces of information, a handle to the hive (_HHIVE) and the Cell Index - a Cell is never pointed to directly. In the PDF by Dr B. Probert, a good technical overview of cells can be found, and the key points are:

- Referenced as a ‘cell index’ (HCELL_INDEX)

- Cell index is offset within the file (minus 0x1000 – the header) – ULONG

- Size rounded at 8 bytes boundary

- If Index & 1<<31 , then the cell is Volatile ; Else Permanent

- If Cell.Size >= 0 , Cell.Status = Free ; Else Cell.Status = Allocated && Cell.RealSize = -Cell.Size

As for the exact type, ReactOS helps us with the exact definition:

typedef ULONG HCELL_INDEX, *PHCELL_INDEX;

So the cell index is a ULONG, which can be decomposed as a bitmask that allows to determine more information such as the cell Type (Permanent vs Volatile) and the Block; information which can be extracted from the Index as such:

#define HvGetCellType(Cell) ((ULONG)(((Cell) & HCELL_TYPE_MASK) >> HCELL_TYPE_SHIFT))

#define HvGetCellBlock(Cell) ((ULONG)(((Cell) & HCELL_BLOCK_MASK) >> HCELL_BLOCK_SHIFT))

Now how do we go from the key node to a cell, assuming we have a hive handle and an index? Remember above when we mentioned that the procedure to get to the cell is a function pointer inside the hive handle: nt!_HHIVE.GetCellRoutine? Well, that’s how. Also interestingly, all the hive handles are pointing to the same function nt!HvpGetCellPaged, although it doesn’t have to be the case:

0: kd> dt _HHIVE

nt!_HHIVE

+0x000 Signature : Uint4B // 0xbee0bee0

+0x008 GetCellRoutine : Ptr64 _CELL_DATA*

+0x010 ReleaseCellRoutine : Ptr64 void

+0x018 Allocate : Ptr64 void*

+0x020 Free : Ptr64 void

[...]

0: kd> dx -g @$hives.Select( h => new { HiveName=h.HiveRootPath, CellRoutine=h.Hive.GetCellRoutine} )

====================================================================================================

= = (+) HiveName = (+) CellRoutine =

====================================================================================================

= [0x0] - "" - 0xfffff8054248e880 =

= [0x1] - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SYSTEM" - 0xfffff8054248e880 =

= [0x2] - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\HARDWARE" - 0xfffff8054248e880 =

= [0x3] - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SOFTWARE" - 0xfffff8054248e880 =

= [0x4] - "\REGISTRY\MACHINE\BCD00000000" - 0xfffff8054248e880 =

[...]

0: kd> .printf "%y\n", 0xfffff8054248e880

nt!HvpGetCellPaged (fffff805`4248e880)

By reversing it in IDA, it reveals the exact behavior for fetching cells (below shown in a simplified pseudo-C code):

_CELL_DATA *__fastcall HvpGetCellPaged(_HHIVE *hive, unsigned int CellIndex, _HV_GET_CELL_CONTEXT *ctx)

{

_HMAP_ENTRY *Entry;

PVOID BinAddress;

PVOID CellAddress;

_CELL_DATA *CellResult;

[...]

Entry = &hive->Storage[CellIndex >> 31].Map->Directory[(CellIndex >> 21) & 0x3FF]->Table[(CellIndex >> 12) & 0x1FF];

BinAddress = Entry->PermanentBinAddress;

[...]

CellAddress = Entry->BlockOffset + (BinAddress & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0ui64) + (CellIndex & 0xFFF);

[...]

CellResult = (_CELL_DATA *)(CellAddress + 4); // *CellAddress contains the size field as ULONG

[...]

return CellResult;

}

With that in mind, we can craft an equivalent function GetCellAddress that we can use in WinDbg, which given a hive handle and an index will return the cell address in memory (in WinDbg JS):

function GetCellAddress(KeyHive, Index)

{

let Type = GetCellType(Index);

let Table = GetCellTable(Index);

let Block = GetCellBlock(Index);

let Offset = GetCellOffset(Index);

let MapDirectory = KeyHive.Storage[Type].Map;

let MapTableEntry = MapDirectory.Directory[Table];

let Entry = host.createPointerObject(MapTableEntry.address.add(Block * sizeof("nt!_HMAP_ENTRY")), "nt", "_HMAP_ENTRY*");

let BinAddress = Entry.PermanentBinAddress.bitwiseAnd(~0x0f);

let CellAddress = BinAddress.add(Entry.BlockOffset).add(Offset);

return CellAddress;

}

Such function is critical to navigate correctly in the hive, and we’ll refer to it in the rest of the article as GetCellAddress(). If you remember the lookup slide, you’ll realize that the function is “incorrect”: in its state it’ll return the address of the beginning of the Cell, which holds the size (as a ULONG). Therefore to get the address of the data of the Cell, simply add sizeof(ULONG) (or 4) to the result.

It was interesting to me to find that the engineers behind the CM have decided to go with this function pointer approach for hives, instead of a static one but couldn’t find one (if you know, let me know!). And hey, it makes any form of kernel hooking for the registry a lot easier so it’s great for us!

Enumerating Values

Now that we’ve understood the logic behind Cells and how to navigate through them, the rest is easier to understand. As we’ve mentioned before, “Key Values” are roughly the equivalent of a regular filesystem files. To get the values of a specific key node, one can use the field nt!_CM_KEY_NODE.ValueList (of type _CHILD_LIST) we’ve briefly discussed above.

0: kd> dt _CHILD_LIST

nt!_CHILD_LIST

+0x000 Count : Uint4B

+0x004 List : Uint4B

Then it’s as simple as it gets: the structure gives us the number of values and the Cell Index of the array (of the form of an array of size _CHILD_LIST.Count x sizeof(HCELL_INDEX)) of all the values of this key node. Then we simply iterate through the list of HCELL_INDEX using GetCellAddress(KeyHive, Index) to get the Key Nodes of type CM_KEY_VALUE_SIGNATURE: the type CM_KEY_VALUE_SIGNATURE will indicate that the current node has a structure of nt!_CM_KEY_VALUE, where the actual content and content length can be read.

0: kd> dt _CM_KEY_VALUE

nt!_CM_KEY_VALUE

+0x000 Signature : Uint2B

+0x002 NameLength : Uint2B

+0x004 DataLength : Uint4B

+0x008 Data : Uint4B

+0x00c Type : Uint4B

+0x010 Flags : Uint2B

+0x012 Spare : Uint2B

+0x014 Name : [1] Wchar

_CM_KEY_VALUE.Data doesn’t contain a pointer to the data, but again an HCELL_INDEX: so we need to call again GetCellAddress() on this index (we stay on the same hive), and finally retrieve the data.

Enumerating SubKeys

By knowing how cells work it is possible to know how subkeys will be linked: subkeys are just _CM_KEY_NODE objects. the structure gives 2 fields

+0x014 SubKeyCounts : [2] Uint4B

+0x01c SubKeyLists : [2] Uint4B

The important one is SubKeyLists which is an array of 2 (… you guessed it …) Cell Indexes (HCELL_INDEX). The reasons each array has 2 entries, is to differentiate between Permanent SubKeys (at index 0), and Volatile subKeys (at index 1). To iterate through a tree, there needs to be a root. And the hive root node cell index is given by the field RootCell of the _HBASE_BLOCK, which the hive handle always holds a reference to, via the BaseBlock field:

As we shown before from the linked list of _CMHIVE from nt!CmpHiveListHead we can iterate through all the system hives. Each hive object has a pointer to a handle of hive (_HHIVE) which exposes a _DUAL field named Storage: the index 0 is used for permanent storage, index 1 for volatile

0: kd> dt _DUAL

nt!_DUAL

+0x000 Length : Uint4B

+0x008 Map : Ptr64 _HMAP_DIRECTORY

+0x010 SmallDir : Ptr64 _HMAP_TABLE

+0x018 Guard : Uint4B

+0x020 FreeDisplay : [24] _FREE_DISPLAY

+0x260 FreeBins : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x270 FreeSummary : Uint4B

To summarize more graphically

The subkeys will be located in the Map element (of type _HMAP_DIRECTORY). The _HMAP_DIRECTORY structure simply contains 1 element, a table of 1024 _HMAP_TABLE, each of them structured of 1 element: a Table of 512 _HMAP_ENTRY.

0: kd> dt _HMAP_DIRECTORY

nt!_HMAP_DIRECTORY

+0x000 Directory : [1024] Ptr64 _HMAP_TABLE

0: kd> dt _HMAP_TABLE

nt!_HMAP_TABLE

+0x000 Table : [512] _HMAP_ENTRY

0: kd> dt _HMAP_ENTRY

nt!_HMAP_ENTRY

+0x000 BlockOffset : Uint8B

+0x008 PermanentBinAddress : Uint8B

+0x010 MemAlloc : Uint4B

The last nibble of PermanentBinAddress is used for meta-data, so we can bitwise AND it with ~0xf. Finally to access the data, we simply must add the BlockOffset value, and the final Offset retrieved from AND-ing the Index to 0xfff. This is a the behavior that the function GetCellAddress() will do for us to painlessly get the virtual address of a cell, just from a hive handle and an Index.

Put it all together

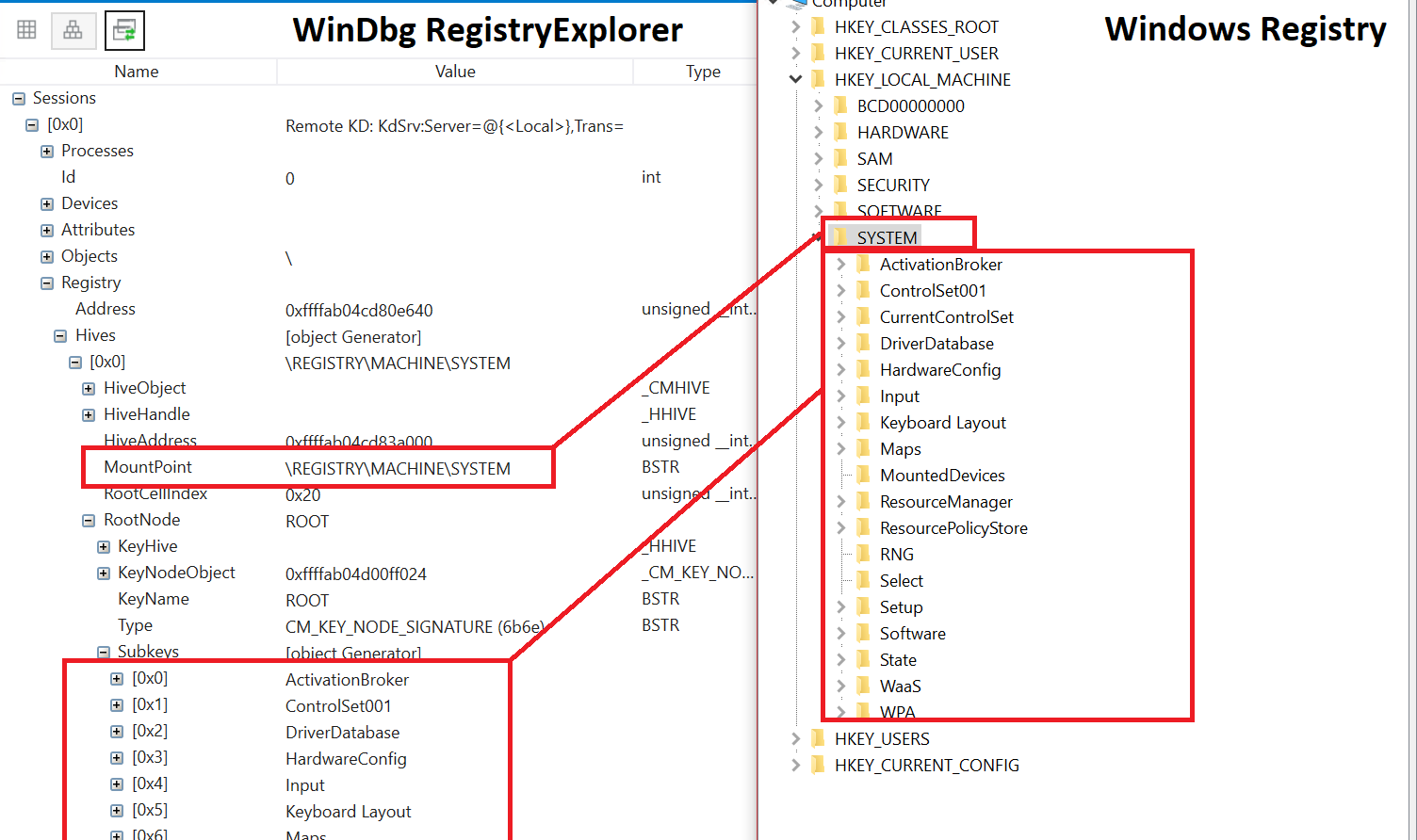

As a learning exercise, I always try to build a script/tool when digging into a topic, and here the result is another WinDbg JS script, RegistryExplorer.js[1] which will allow to navigate through the registry using WinDbg Debugger Data Model (and therefore also query it via LINQ)

a better version was done by @msuiche here[^3]

Example:

0: kd> dx @$cursession.Registry.Hives

@$cursession.Registry.Hives : [object Generator]

[0x0] : \REGISTRY\MACHINE\SYSTEM

[0x1] : \REGISTRY\MACHINE\HARDWARE

[0x2] : \REGISTRY\MACHINE\BCD00000000

[0x3] : \REGISTRY\MACHINE\SOFTWARE

[0x4] : \REGISTRY\USER\.DEFAULT

[0x5] : \REGISTRY\MACHINE\SECURITY

[...]

0: kd> dx @$cursession.Registry.Hives.Where( x => x.Name == "HARDWARE" ).First()

@$cursession.Registry.Hives.Where( x => x.Name == "HARDWARE" ).First() : \REGISTRY\MACHINE\HARDWARE

HiveObject [Type: _CMHIVE]

HiveHandle [Type: _HHIVE]

HiveAddress : 0xffffcf0289744000

MountPoint : \REGISTRY\MACHINE\HARDWARE

RootCellIndex : 0x20

RootNode : HARDWARE

Name : HARDWARE

Or the click-friendly version 😀

Practical Toy Example: dumping SAM

Any beginner pentester would (should?) know that in user-mode, a local Administrator account has enough privilege to dump the SAM & SYSTEM hives from the command line using reg.exe: (* If you didn’t know, I’d suggest reading this[3] ASAP)

PS C:\WINDOWS\system32> reg.exe save HKLM\SAM C:\Temp\SAM.bkp

The operation completed successfully.

Same goes for SYSTEM.

However, even as Administrator trying to access using regedit.exe the subkeys of HLKM\SECURITY and SAM will be denied as they require NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM privilege which is only a half protection, as psexec /s would be enough to bypass it. So with that in mind, in theory, RegistryExplorer.js gives us everything we need to fetch those values.

And then real life strikes…

Issue #1

As I was trying to get those values manually, the initial script failed (crashed) complaining there was an invalid access to user-mode memory:

GetCellDataAddress(Hive=ffffab04d1191000, Index=32): type=0 table=0 block=0 offset=32

[0x0] : Unable to read target memory at '0x280f6fa1850' in method 'readMemoryValues' [at registryexplorer (line 20 col 18)]

It seemed that the cells for accessing the SAM were at some points hitting user-mode area, in a process different than System, so the address access walking the wrong page table, and hence the exception from WinDbg. Which got immediately confirmed:

0: kd> dt _hmap_entry ffffab04d1191000

nt!_HMAP_ENTRY

+0x000 BlockOffset : 0

+0x008 PermanentBinAddress : 0x00000280`f6fa1001 <<< yup here, in UM

+0x010 MemAlloc : 0x1000

Then how does the kernel know where to fetch this information? Well it turned out that the hive handle can hold reference to a process in its ViewMap.ProcessTuple attribute, of type _CMSI_PROCESS_TUPLE which holds both a handle to the _EPROCESS and a pointer to the _EPROCESS. We can use that information to determine the backing process:

0: kd> dt _hhive ffffab04d1191000 ViewMap.ProcessTuple

nt!_HHIVE

+0x0d8 ViewMap :

+0x018 ProcessTuple : 0xfffff805`422657c0 _CMSI_PROCESS_TUPLE

0: kd> dx ((_CMSI_PROCESS_TUPLE*)0xfffff805`422657c0)->ProcessReference

((_CMSI_PROCESS_TUPLE*)0xfffff805`422657c0)->ProcessReference : 0xffff828d85dbd080 [Type: void *]

0: kd> dx @$cursession.Processes.Where( x => &(x.KernelObject) == (_EPROCESS*)0xffff828d85dbd080)

@$cursession.Processes.Where( x => &(x.KernelObject) == (_EPROCESS*)0xffff828d85dbd080)

[0x54] : Registry [Switch To]

It points to the Registry process, which makes sense. To confirm, we can switch to the context of the process, and try to re-access the UM address 0x280f6fa1850:

0: kd> dx -s @$cursession.Processes.Where( x => x.Name == "Registry").First().SwitchTo()

0: kd> db 0x280f6fa1850

00000280`f6fa1850 a8 ff ff ff 6e 6b 20 00-4a 92 fb 8e 6b 38 d5 01 ....nk .J...k8..

00000280`f6fa1860 03 00 00 00 c0 02 00 00-06 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

00000280`f6fa1870 a0 1f 00 00 ff ff ff ff-01 00 00 00 28 2c 00 00 ............(,..

[...]

The signature kn (0x6b6e) at 0x280f6fa1850+sizeof(ULONG) confirms we’re hitting the right spot.

Issue #2

Now I could access some keys & values but not everything:

0: kd> dx @$SamHive = @$cursession.Registry.Hives.Where( x => x.MountPoint.EndsWith("SAM")).First()

0: kd> dx @$SamHive.RootNode.Subkeys[0].Subkeys[0].Subkeys.Where(x => x.KeyName == "Account").First().Subkeys

@$SamHive.RootNode.Subkeys[0].Subkeys[0].Subkeys.Where(x => x.KeyName == "Account").First().Subkeys : [object Generator]

[0x0] : Aliases

[0x1] : Groups

[0x2] : Users

The 2nd issue faced was that when trying to access some keys in UM for the HKLM\SAM hive, WinDbg would inconsistently return some access violation error. This reason was somewhat easier to figure out the cause, less easy for a programmatic remediation.

0: kd> dx @$cursession.Registry.Hives.Where( x => x.MountPoint.EndsWith("SAM")).First().RootNode.Subkeys[0].Subkeys[0].Subkeys.Where(x => x.KeyName == "Account").First().Subkeys[2].Subkeys

@$cursession.Registry.Hives.Where( x => x.MountPoint.EndsWith("SAM")).First().RootNode.Subkeys[0].Subkeys[0].Subkeys.Where(x => x.KeyName == "Account").First().Subkeys[2].Subkeys : [object Generator]

GetCellDataAddress(Hive=ffffab04d1191000, Index=8096) = 280f6fa2fa0

[0x0] : Unable to read target memory at '0x280f6fa2fa4' in method 'readMemoryValues' [at registryexplorer (line 20 col 18)]

The cause behind it was not the calculation method of the Cell address but due to the fact that the page was paged out. The clue for me was the fact the missing is usually surrounded by other mapped pages.

0: kd> db 280f6fa2fa0

00000280`f6fa2fa0 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ??-?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ????????????????

00000280`f6fa2fb0 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ??-?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ????????????????

00000280`f6fa2fc0 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ??-?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ????????????????

00000280`f6fa2fd0 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ??-?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ????????????????

00000280`f6fa2fe0 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ??-?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ????????????????

00000280`f6fa2ff0 ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ??-?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ?? ????????????????

00000280`f6fa3000 fe a3 d4 01 ff ff ff ff-ff ff ff 7f 57 8a 70 38 ............W.p8

00000280`f6fa3010 c8 b0 d6 01 e9 03 00 00-01 02 00 00 14 02 00 00 ................

I didn’t find a way to solve this programmatically (i.e. force WinDbg to page-in), although just a reboot is enough to make sure the desired pages are still in memory. Then we can finally access the keys and values:

0: kd> dx @$UserEncryptedPasswords = @$cursession.Registry.Hives.Where( x => x.MountPoint.EndsWith("SAM")).First().RootNode.Subkeys[0].Subkeys[0].Subkeys.Where(x => x.KeyName == "Account").First().Subkeys[2].Subkeys

@$cursession.Registry.Hives.Where( x => x.MountPoint.EndsWith("SAM")).First().RootNode.Subkeys[0].Subkeys[0].Subkeys.Where(x => x.KeyName == "Account").First().Subkeys[2].Subkeys : [object Generator]

[0x0] : 000001F4

[0x1] : 000001F5

[0x2] : 000001F7

[0x3] : 000001F8

[0x4] : 000003E9

[0x5] : Names

So then to dump the keys for the Administrator (UID=500=0x1f4)

0: kd> dx @$UserEncryptedPasswords[0].Values

@$UserEncryptedPasswords[0].Values : [object Generator]

[0x0] : F

[0x1] : V

[0x2] : SupplementalCredentials

0: kd> dx @$UserEncryptedPasswords[0].Values[0]

dx @$UserEncryptedPasswords[0].Values[0] : F

KeyHive [Type: _HHIVE]

KeyValueObject : 0x271ee85192c [Type: _CM_KEY_VALUE *]

KeyName : F

KeyDataType : REG_BINARY

KeyDataSize : 0x50

Type : CM_KEY_VALUE_SIGNATURE (6b76)

KeyDataRaw : 3,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,...

And done, we’ve got the data! We can now totally navigate the Registry from a KD session!

Outro

Understanding those bits of the CM took more work than I imagined, but as it was nicely engineered, it was fun to go through. The CM is way more complex than that, but this is the basics: we didn’t cover more advanced stuff like the use of the .LOG file, the memory management of the CM and other funkiness, but I hope this article was interesting and useful to you and thanks for making it this far.

Peace out ✌

References

-

comaeio/SwishDbgExt -

reactos/reactos - Windows Internals 6th - Part 1, Chapter 4: Management Mechanism - The Registry

- Enumerating Registry Hives - moyix