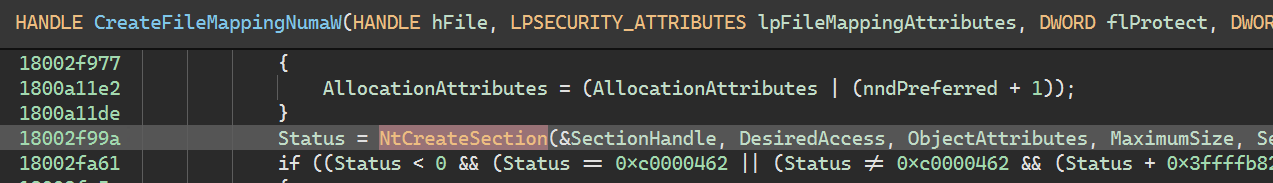

I’ve recently decided to read cover to cover some Windows Internals books, and currently reading the amazing book “What Makes It Page”, it gave me some ideas to play with Section Objects as they covered in great details. One thought that occurred to me was that even though a section is created from user or kernel land, its mapping can be in user-mode as much as in kernel (when called from the kernel).

Windows Section Objects

For quick reminder, a Section Object on Windows is a specific type of kernel object (of structure nt!SECTION) that represents a block of memory that processes can share between themselves or between a process and the kernel. It can be mapped to the paging file (i.e. backed by memory) or to a file on disk, but either can be handled using the same set of API, and even though they are allocated by the Object Manager, it is one of the many jobs of the Memory Manager to handle their access (handle access, permission, mapping etc.). In usermode the high level API is kernel32!CreateFileMapping, which after some hoops into kernelbase, boils down to ntdll!NtCreateSection

The signature is as follow:

NTSTATUS

NTAPI

NtCreateSection (

_Out_ PHANDLE SectionHandle,

_In_ ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess,

_In_opt_ POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes,

_In_opt_ PLARGE_INTEGER MaximumSize,

_In_ ULONG SectionPageProtection,

_In_ ULONG AllocationAttributes,

_In_opt_ HANDLE FileHandle

);

If successful, the syscall will return a section handle in SectionHandle, which will refer to an instance of a nt!_SECTION. Therefore the handle will be added to the handle table of the calling process, accessible from kernel and user modes unless OBJ_KERNEL_HANDLE is specified in the ObjectAttributes. This will be important for us in the following, because it implies that if the process terminates, so will the section object.

In itself the Section Object doesn’t have a lot going on, unless it is mapped to memory. This is achieved through kernel32!MapViewOfView(Ex) which again, boils down to the syscall ntdll!NtMapViewOfSection, whose signature is as follow:

//

// Syscall entry point

//

NTSTATUS

NTAPI

NtMapViewOfSection(

HANDLE SectionHandle,

HANDLE ProcessHandle,

PVOID *BaseAddress,

ULONG_PTR ZeroBits,

SIZE_T CommitSize,

PLARGE_INTEGER SectionOffset,

PSIZE_T ViewSize,

SECTION_INHERIT InheritDisposition,

ULONG AllocationType,

ULONG Win32Protect)

Reversing this function is relatively straight forward:

{

[...]

if ( NT_SUCCESS(MiValidateZeroBits(&ZeroBits)) )

{

AccessMode = KeGetCurrentThread()->PreviousMode;

//

// Internal function to the Memory Manager to map a view of a section

//

Status = MiMapViewOfSectionCommon(

ProcessHandle,

SectionHandle,

0,

BaseAddress,

ViewSize,

SectionOffset,

Win32Protect,

ZeroBits,

AccessMode,

&SectionParameter);

[...]

which makes us jump to:

NTSTATUS MiMapViewOfSectionCommon(

HANDLE ProcessHandle,

HANDLE SectionHandle,

ACCESS_MASK DesiredAccess,

PVOID BaseAddress,

uint64_t ViewSize,

uint64_t SectionOffset,

uint32_t Win32Protect,

uint8_t ZeroBits,

KPROCESSOR_MODE AccessMode,

SECTION_PARAMETER *SectionParameter)

{

[...]

//

// Get a reference to the asking process

//

Status = ObpReferenceObjectByHandleWithTag(ProcessHandle, (DesiredAccess + 8), ProcessType, AccessMode, 'MmVw', &SectionParameter->ProcessObject, nullptr, nullptr);

if (Status >= 0)

{

PSECTION* SectionObject = nullptr;

pSectionObject = &SectionObject;

//

// Get a reference to the section

//

Status = ObReferenceObjectByHandle(SectionHandle, &MmMakeSectionAccess[((uint64_t)SectionParameter->ProtectMaskForAccess)], MmSectionObjectType, AccessMode, pSectionObject, nullptr);

SectionParameter->SectionObject = SectionObject;

if (Status < 0)

{

ObfDereferenceObjectWithTag(SectionParameter->ProcessObject, 'MmVw');

}

}

[...]

if (AccessMode == KernelMode)

{

//

// In KM, do whatever

//

ViewSize_1 = ViewSize;

}

else

{

PVOID* pBaseAddress_1 = BaseAddress;

//

// With a request coming from UM, validate the BaseAddress is within UM bounds

//

if (BaseAddress >= 0x7fffffff0000)

{

pBaseAddress_1 = 0x7fffffff0000;

}

*(int64_t*)pBaseAddress_1 = *(int64_t*)pBaseAddress_1;

ViewSize_1 = ViewSize;

uint64_t r8_2 = ViewSize_1;

if (ViewSize_1 >= 0x7fffffff0000)

{

r8_2 = 0x7fffffff0000;

}

*(int64_t*)r8_2 = *(int64_t*)r8_2;

}

SectionParameter->BaseAddress = *(int64_t*)BaseAddress;

SectionParameter->ViewSize = *(int64_t*)ViewSize_1;

[...]

}

What matters the most here would be the BaseAddress argument which will hold the UM address of the mapping. Meaning that Section Objects can be used to create communication channels between kernel <-> user mode (on top of obviously user <-> user). This is particularly nice especially because it allows to control finely the permission to the area: for instance a driver could create a section as read-writable, map its own view as RW, but expose to any process as RO. As a matter of fact, this is exactly how Windows 11 decided to protect the (K)USER_SHARED_DATA memory region, frequently used by kernel exploit since it’s read/writable in ring-0 at a well-known address, making it a perfect way to bypass ALSR. The protection was added in 22H1 global variable which is initialized at boot-time and mapped as RW from the kernel through the nt!MmWriteableUserSharedData; however from user-mode only a read-only view is exposed to processes. For complete details about that protection, I invite the reader to refer to Connor McGarr’s in-depth excellent blog post on the subject.

Section Object as a Kernel/User Communication Vector

Purely coincidentally, a colleague of mine stumbled upon a problem where they wanted to be able to capture the user-mode context of a thread from a driver, through PsGetThreadContext. The tricky part here was that PsGetThreadContext() follows the following signature:

NTSTATUS

PSAPI

PsGetThreadContext(

IN PETHREAD Thread,

IN OUT PCONTEXT ThreadContext,

IN KPROCESSOR_MODE PreviousMode

);

Where ThreadContext is the linear address to write the thread CONTEXT passed as first argument. However, the 3rd argument, PreviousMode matters the most: if specified as UserMode (1), the function performs a check to make sure the ThreadContext linear address resides within the usermode address range. Since I really love turning theory into practice, I figured this would be a perfect practice case for the technique mentioned above, so I ended up writing a PoC driver to serve that purpose in a (IMHO) fairly nice way. This actually didn’t take long thanks to my driver template and all I had to do was implement the steps which were:

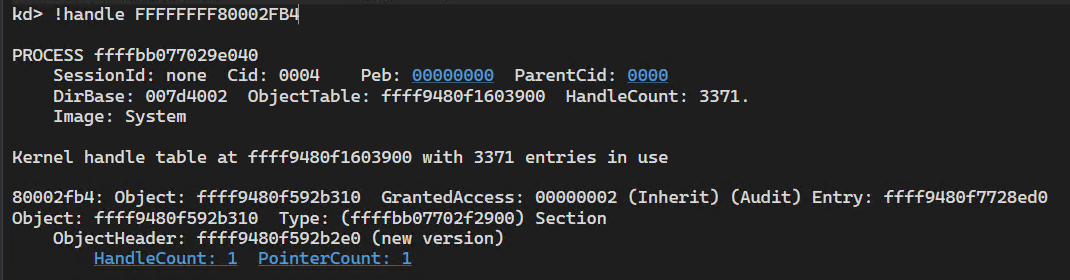

- Create a section in the

Systemprocess. Why inSystem? Simply because section handles must be tight to a process: therefore if the section is created in a “normal” process, the handle to it will be close when/if said process terminates, effectively closing the section. So we can use theDriverEntryto make sure the section handle is stored in theSystemkernel handle table. Save the handle in a global variable.

// create section

{

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oa {};

InitializeObjectAttributes(

&oa,

nullptr,

OBJ_EXCLUSIVE | OBJ_KERNEL_HANDLE | OBJ_FORCE_ACCESS_CHECK,

nullptr,

nullptr);

LARGE_INTEGER li {.QuadPart = 0x1000};

Status =

::ZwCreateSection(&Globals.SectionHandle, SECTION_MAP_WRITE, &oa, &li, PAGE_READWRITE, SEC_COMMIT, NULL);

EXIT_IF_FAILED(L"ZwCreateSection");

}

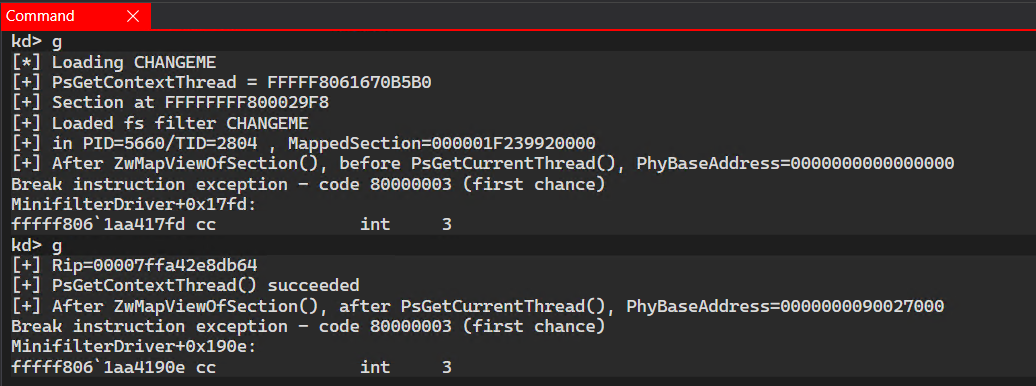

By breakpointing at the end of DriverEntry we confirm that the handle resides in the System process.

[*] Loading CHANGEME

[+] PsGetContextThread = FFFFF8061670B5B0

[+] Section at FFFFFFFF80002FB4

[+] Loaded fs filter CHANGEME

Break instruction exception - code 80000003 (first chance)

MinifilterDriver+0x7275:

fffff806`1aa57275 cc int 3

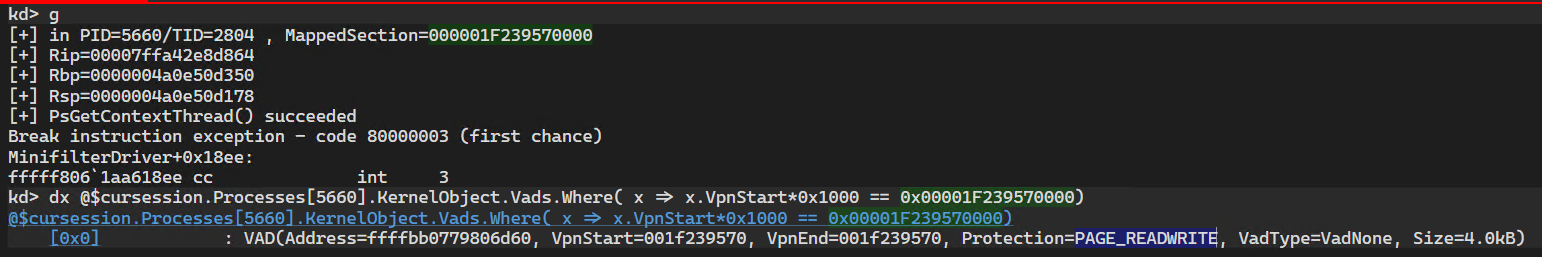

- Then I can use any callback (process/image notification, minifilter callbacks etc.) to invoke

ZwMapViewOfSection, reusing the section handle from the step earlier, andNtCurrentProcess()as process handle.

NTSTATUS Status = ::ZwMapViewOfSection(

Globals.SectionHandle,

NtCurrentProcess(),

&BaseAddress,

0L,

0L,

NULL,

&ViewSize,

ViewUnmap,

0L,

PAGE_READWRITE);

EXIT_IF_FAILED(L"ZwMapViewOfSection");

BaseAddress will return an 64KB-aligned address located randomly (ASLR). The best thing here, is that we also control ZeroBits, allowing to (partly) control where that address will land.

- We’re free to call

PsGetThreadContext()with the returnedBaseAddressvalue.

PCONTEXT ctx = reinterpret_cast<PCONTEXT>(BaseAddress);

ctx->ContextFlags = CONTEXT_FULL;

Status = Globals.PsGetContextThread(PsGetCurrentThread(), ctx, UserMode);

EXIT_IF_FAILED(L"PsGetContextThread");

DbgBreakPoint();

To prevent any inadverted permission drop of the view (and therefore BSoD-ing us during the call to PsGetThreadContext), we can secure the location using MmSecureVirtualMemory.

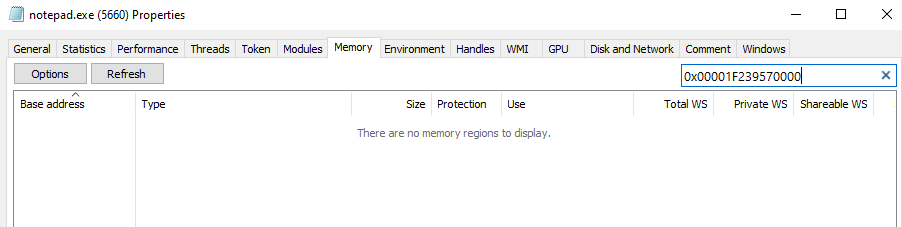

From WinDbg we can confirm the VAD is mapped when the breakpoint is hit:

And as soon as the syscall returns, we’re unmapped:

- Close the section in the driver unload callback.

That’s pretty much it: what we’ve got at the end is kernel driver controlled communication vector to any process in usermode: as the section handle is part of System kernel handle table, it’s untouchable from ring-3 unless the driver dictates otherwise by creating a view (with proper permissions) to it. This approach is great as it allows the driver to control everything, but if we want to give a user-mode process some say into it, it’s also possible simply by turning the anonymous section we created for this PoC into a named one, then call sequentially OpenFileMapping(SectionName) then MapViewOfFile(). In addition, it could very well be ported to a process <-> process communication but here I wanted to play with the minifilter callbacks as an on-demand mechanism.

Side-track

The careful reader will have notice that the step introduce a tiny race condition window, where another thread can also access the memory region. That bothered me, so I also examined more advanced options relying on the shared section objects. By nature they involve 2 PTEs:

- the “real” PTE (hardware PTE), effectively used for VA -> PA translation;

- along with a prototype PTE.

When the view is created, the memory manager will create empty PTEs but expect a page fault. This is verified quickly by breaking right after the call to ZwMapViewOfSection

[*] Loading CHANGEME

[+] PsGetContextThread = FFFFF8061670B5B0

[+] Section at FFFFFFFF800035E4

[+] Loaded fs filter CHANGEME

[+] in PID=3292/TID=4676 , MappedSection=0000018D40BF0000

Break instruction exception - code 80000003 (first chance)

MinifilterDriver+0x17a7:

fffff806`1aa517a7 cc int 3

kd> !pte2 0x000018D40BF0000

@$pte2(0x000018D40BF0000)

va : 0x18d40bf0000

cr3 : 0x3e64d000

pml4e_offset : 0x3

pdpe_offset : 0x35

pde_offset : 0x5

cr3_flags : [- -]

pml4e : PDE(PA=3e66d000, PFN=3e66d, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

pdpe : PDE(PA=3df0e000, PFN=3df0e, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

pde : PDE(PA=d97b6000, PFN=d97b6, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

pte_offset : 0x1f0

pte : PTE(PA=0, PFN=0, Flags=[- RO K - - - - - -])

kernel_pxe : 0xffffeb00c6a05f80

kd> dx -r1 @$pte2(0x000018D40BF0000).pte

@$pte2(0x000018D40BF0000).pte : PTE(PA=0, PFN=0, Flags=[- RO K - - - - - -])

address : 0xd97b6f80

value : 0x0

[...]

PhysicalPageAddress : 0x0

Pte : 0x0 [Type: _MMPTE *] <<<<

However, after the call to PsGetThreadContext the entry is correctly populated:

kd> g

[+] Rip=00007ffa42e8d724

[+] Rbp=00000020eccff550

[+] Rsp=00000020eccff448

[+] Rax=0000000000000033

[+] Rbx=0000000000214040

[+] Rcx=00000020eccff490

[+] Rdx=0000000000100080

[+] Rdx=0000000000100080

[+] PsGetContextThread() succeeded

Break instruction exception - code 80000003 (first chance)

MinifilterDriver+0x1936:

fffff806`1aa51936 cc int 3

kd> dx -r1 @$pte2(0x000018D40BF0000)

@$pte2(0x000018D40BF0000) : VA=0x18d40bf0000, PA=0xe23a0000, Offset=0x0

va : 0x18d40bf0000

cr3 : 0x3e64d000

pml4e_offset : 0x3

pdpe_offset : 0x35

pde_offset : 0x5

cr3_flags : [- -]

pml4e : PDE(PA=3e66d000, PFN=3e66d, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

pdpe : PDE(PA=3df0e000, PFN=3df0e, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

pde : PDE(PA=d97b6000, PFN=d97b6, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

pte_offset : 0x1f0

pte : PTE(PA=e23a0000, PFN=e23a0, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

offset : 0x0

pa : 0xe23a0000

kernel_pxe : 0xffffeb00c6a05f80

The PTE is valid:

kd> dx -r1 @$pte2(0x000018D40BF0000).pte

@$pte2(0x000018D40BF0000).pte : PTE(PA=e23a0000, PFN=e23a0, Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -])

address : 0xd97b6f80

value : 0xc0000000e23a0867

Flags : Flags=[P RW U - - A D - -]

PageFrameNumber : 0xe23a0

Pfn [Type: _MMPFN]

PhysicalPageAddress : 0xe23a0000

Pte : 0xffff9480f55f81d0 [Type: _MMPTE *]

So this means we have a great way to determine whether a physical page was accessed, using MmGetPhysicalAddress(). To test this we invoke it after the mapping (where we expect a null value) and a second time after the call to PsGetThreadContext:

The 2nd value for PhyBaseAddress points to the physical address where the function output is stored. At that point, I thought it would be sufficient to stop because we have an effective way to honeypot potential corruptions attempts:

- Create a section with many pages (the more the better)

- During the preparation to the invocation of

PsGetThreadContext, choose randomly one page that will receive theCONTEXT - Map all the pages separately

- Call

PsGetThreadContext

Once the call is over, we can use the method above to validate whether any other page than the one we know valid were accessed. If so, discard the result.

Isn’t Windows awesome?

End

There are a lot of possible fun uses of sections, and since I want to try to document more of my “stuff”. Some offensive cool use case would be for instance, would be to expose code “on-demand” to a specific thread/process, removing the mapped execution page(s) from the process VAD as soon as we’re done. I’ll try to post follow-up updates.

For those interested in the code, you would find a minifilter driver ready to build & compile on the Github project: hugsy/shared-kernel-user-section-driver

So, see you next time?

Credits & References: